i. Short takes

ii. Portraits of the artist as a young man x2

iii. On the proliferation of nostalgia-driven restaurants

TOP GUN: MAVERICK (Joseph Kosinsky, 2022): An expensive bid to stay young and remain in the public eye, producer-star extraordinaire Tom Cruise seems incapable of coming to terms with middle age. He endeavors to defy time and fate in this sequel, as jingoistic as the original, by recasting himself as the savior, sole survivor, and hero, instead of passing the baton to a younger heir.

RISKY BUSINESS (Paul Brickman, 1983): This treats what is a rather uproarious plot line with defiant solemnity. A posh high school teen in a tony Chicago suburb becomes a pimp and transforms his mansion into a temporary brothel to raise money to replace his dad’s Porsche, which he crashed in an underage joyride. There is probably a better reading of sex work angle, but I was caught off guard by seeing Joe Pantoliano with hair.

FUNNY PAGES

Owen Kline

My youngest brother used to have a graphic tee from some small streetwear brand with a hand drawn skeleton being guillotined by the grim reaper or some such with a caption that read “Life’s a joke and this is the punchline.” Too crass for the public taste, but not far enough on the fringes to cause concern, it elicited nasty glares from passersby on the subway or a satisfied chortle from the likeminded. I thought of this lewdly misanthropic (and, not altogether incorrect) shirt, as I watched Funny Pages, a puckishly coming-of-age story about an aspiring comic-book artist distributed by A24 that cynicism with the same unseemly relish.

After the freak-accident death of his art teacher and mentor, a privileged suburban teen (Daniel Zholgadri) spurns all manner of creature comforts to focus on his craft. His name is Robert, and he would never deign to call himself a graphic novelist; the preoccupations of his cohort lay more with Archie and Betty than they do with contemporary Marvel. He moves into some sort of illegal basement apartment in Trenton with two much older men—effectively the boiler room that all but forces you to cohabit without a shirt on.

Sean Price Williams, the cinematographer extraordinaire of the indie film world, coats this fetid world with an opaque dust, while Kline populates it with eccentric faces. Funny Pages excels most in transposing the comic book sensibility to film, capturing the goofy and anarchic undertow of the underground. Even the film’s more well-known screen presences, like Maria Dizzia and Josh Pais as Robert’s parents, are also made to feel oddball, but at the same time, their recognizability anchors them as more square. Dizzia particularly is resigned and put off.

It has been a while since we’ve been graced with an off-kilter coming-of-age indie, the edginess of which is appropriately matched, which is to say blinkered, by the protagonist’s expected naïveté. Robert takes on a menial job and encounters a socially hostile low-level color specialist for comics (Matthew Maher) and tries to ask him for lessons. The aspirant-stumbling-on-a-potential mentor-in-the-rough is a common enough through-line for these narratives, but Kline—who plays it safe, or smart—clips the story short in its third act so as not to fault a landing. The truncated denouement (or lack thereof) only further cements the film’s brittleness.

In theaters and VOD.

THE CATHEDRAL

Ricky D’Ambrose

An artist’s development unfolds early in his life, informing his future work. The Cathedral is an autobiographical-ish movie by Ricky D’Ambrose that orbits Jesse Damrosch, a stand-in for the director, starting at birth in 1987 until high school, charting the dissolution of his family on Long Island on the outskirts of middle class.

There is a convoluted family tree that sometimes feels like it requires the simple act of diagramming to fully comprehend, but what is crystal are the sentiments telegraphed (tenderness and reticence) and their prickling effects on Jesse. His father exhibits sharp jolts of imprinting anger, while his mother and her side of are expert at grudges. It is achingly familiar to anyone who’s experienced a childhood unhappiness, victims of low-profile generation-ruffling trauma.

The movie nimbly conveys a mood of nostalgic contemplation but avoids a sense of the mawkish, and idealizing the past, by yoking the personal to the political. The narrative is interwoven with archival footage—vintage posters, recreated photographs, news clips of Desert Storm, Reagan’s death, the occasional commercial—that trace a line to the country’s economic and political history, how it ripples into our quotidian existence.

Even though Jesse (played by three different actors) is the central character, he neither very present nor active, except as an observer, and as far as words go, the film’s dialogue is limited. This is the portrait of an artist as it relates to the inception of his aesthetic POV, presented as a long germination, not a spark of momentous inspiration.

An unnamed and omniscient narrator impartially presides over the film, relaying what’s going on, storybook-style. Coupled with an immaculate photography composed of static shots, the untrained eye might catch a flair of Wes Anderson, but D’Ambrose, who’s already been hard at work melding the fictional and the real in his previous efforts, accomplishes something far more reaching than the dandyism of Anderson-land, which rests on laurels of prim and pretty. Instead, D’Ambrose triumphantly exemplifies a film language forged by Robert Bresson, resulting in a film that is emotionally affecting, even as it is aesthetically distancing. The actors/“models” intone in a studied manner that unexpectedly enhances the emotional heights, and, while the photography is spare, every frame is flush with meaning.

The film’s closeups often encompass limited, but discrete actions—a fan whirling, a lightbulb dimming, and hands (so many hands), grasping paper, curling into the palm—all constituting a sort of synecdoche, each shot a correlative of something larger.

A few more exemplary images:

manicured hands of mothers and aunts dipping eggs into into jewel-toned dyes on Easter as they gossip, a shorthand for congregating women in the kitchen

a hospital tray, segmented with five different kinds of glop, venerates great-aunt Josephine

oil paintings, pastorals, seascapes demonstrate the general balm of the aesthetic for young Jesse

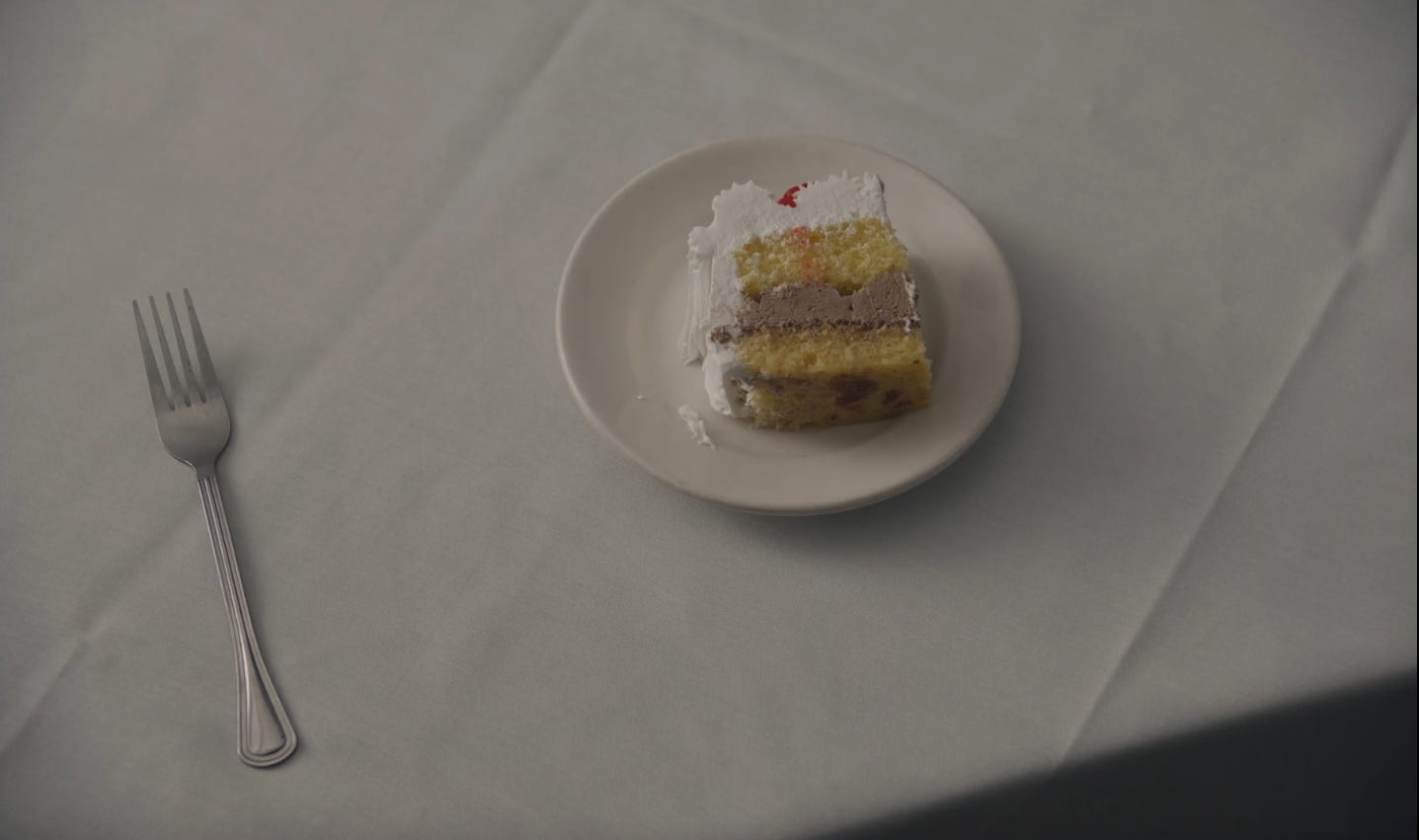

all manner of cakes—presented, sliced, and utensil-razed—indicative of milestone occasions, the arrival and denouement of misbegotten celebrations

The images of food also hold weight because they hearken back to Jesse's father’s culinary vigilance: foreign silverware, potentially tainted, should be cleaned before use, and meat should always be ordered well-done. The cautiousness lends an atmosphere of slow burn anxiety, which would for me plant the seeds for neurosis. The same can be said of the prevalence of money-related scenes (the exchanging bills, the writing of checks), casting the inevitable foundations of a transaction-based American reality, nodding towards the Clinton era boom and its eventual crash.

Streaming exclusively on Mubi. One month free here.

Food has a sense of evoking memory and D’Ambrose does this without the usual conveyances of tastes and arousing appetites. Jesse is watching television and having sliced apples and a triangle of grilled cheese before he is pulled away to learn of his grandmother’s death. The disclosure is bookended by shots of his afternoon snack, tethering an innocuous meal to memory.

Restaurants evoking childhood memories have been cropping up like weeds here, and it's not long until we get aspic and Swedish meatballs as restaurants tire of breading and frying chicken breasts and dip further into the past, someone else’s, for more nostalgia. I still haven’t gone to BERNIE’S in Greenpoint, a North Brooklynized version of TGI Friday—which, really, should tell you everything you need to know. Last I tried, I was quoted a two hour wait… at 5:40pm. Teetering on the perimeter were a group of brunch girls throwing back martinis and a hunched 20-something and his out-of-town mother just beckoned inside for a table. I’m sure he didn’t want to speak to or hear her, because the vibes at Bernie’s operate strongly on that of a raucous bar, that just happens to serve full meals.

CORNER BAR

Corner Bar, a hotel restaurant, is the newest iteration firing perfect, to the point of boring, executions of well-worn staples: steak au poivre; caesar salad (they don’t skimp on the anchovies though); a wan burger (cheddar and an allium-heavy sauce, doesn’t come with fries); the oft-grammed profiterole accompanied by a gravy-boat of chocolate sauce. I had an acceptable meal and got a strong whiff of the “scene,” surrounded by models, some Dimes Square personae, and I even spotted an indie director of their ilk who makes rebellious cinema that I quite like. But I don’t think I’ll be back.

The restaurant is part of a restored Beau-Arts bank, and while the building is historic everything felt a little too new. The servers looked like transplants who stepped out of the Anna Delvey show and the dining room gleamed like a shiny and hollow movie-set, steeped neither in dignity nor personality, at least not yet. I’d rather eat at The Odeon. Invite me here in a few years though, or on your dime—this place was fucking expensive, and for that price tag I crave just little something more.

PATTI ANN’S

I didn’t expect to like Patti Ann’s, since it’s from the same restaurateur behind The Olmstead, my least favorite of the new contemporary American restaurants on Vanderbilt Ave. Though they once got my husband to actively enjoy carrots for the first time in his life, the service is glib and the atmosphere a bit froufrou in that understated way of Prospect Heights stroller moms and their $600 clogs.

Patti Ann’s continues the trend of comfort food, perhaps the zenith of its form with a menu inspired by Midwestern childhood classics. Going a step further, the interior resembles a kindergarten classroom by way of Cracker Barrel—country chairs, a chalkboard wall, shelves of toys, puzzles, assorted knick-knacks for children, maybe not available for purchase.

The food though was quite tasty—how could it not be? The fancy bloomin onion arrives like a colossal lotus, petals unfurling towards a small pot of fancy ranch, which I deigned to eat. The pig in a blanket is singular in both senses of the word: a long slab, a plinth really, of bacon guarded by profoundly buttery pastry. The drinks were fine, but the server mansplained to me the best practices of handling citrus in alcohol. We are all children here, I suppose.