Desert island movies and live-fire cooking

on Triangle of Sadness, octopus, yakitori, and Lina Wertmuller's Swept Away

A colleague and friend recently proffered this revelatory thought-starter: If you were stranded on a desert island, what three dried spices would you want to have stocked in endless supply? Salt has humanely been included, but pepper has not.

Everyone’s responses were fascinating. Z. chose cumin, chili peppers, and oregano. My brother went with Korean chili, ginger, and garlic powders. My answer—black pepper, red pepper, and saffron—evinced staid practicality punctuated by sheer indulgence, which is, coincidentally, how I’d describe the fool-proof foundations of an elite wardrobe, though regrettably not mine. I mean, given a chance to become the beneficiary of an unlimited reserve of the rare and intimate parts of a crocus flower, why not seize it?

i. short takes (terminal island, old, glass onion, swept away)

Ii. triangle of sadness

iii. lobster // octopus

iv. kono yakitori

I don’t have a desert-island movie, the one you’d pack and watch repeatedly, but lately, I’ve noticed many films that take place on such environs. Evoking both the thrill of adventure and the terror of isolation, islands are a place of myth and fantasy. Yet, lurking beneath this utopia is a touch of menace, a reminder of our fragility—mental and physical—and the unpredictability of nature.

This tension is what makes the desert island such a captivating setting for cinema, particularly when it comes to exploring class and social divisions. An island is the ultimate equalizer, stripping us of the quotidian armor of our materialism and leaving us to fend for ourselves in a primal state. With that in mind, let’s hop through a few movies that give White Lotus a run for its money.

TERMINAL ISLAND

Stephanie Rothman, 1973

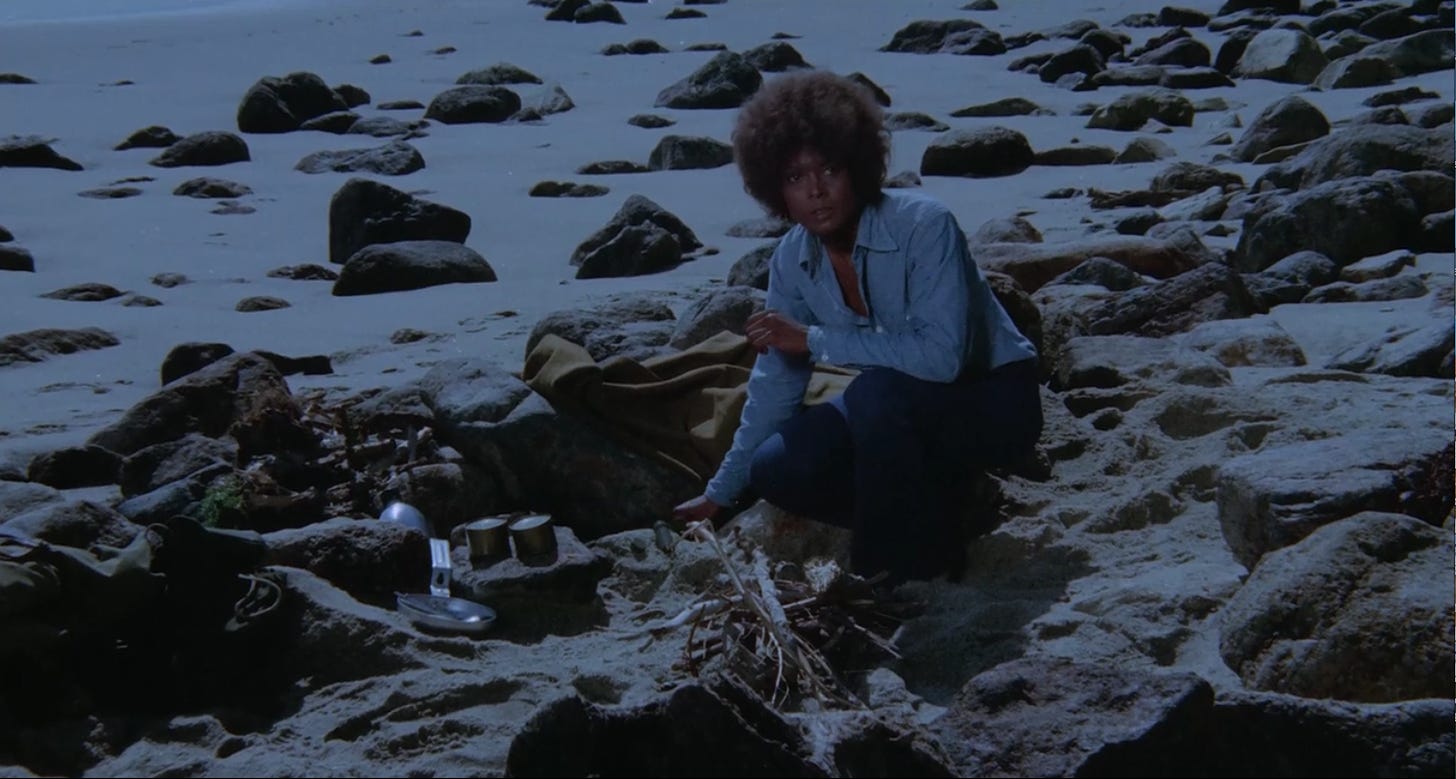

With the death penalty no longer in play, convicted murderers are banished to a remote island where they duke it out like they’re on Survivor, except there is no million dollar prize, or more suitably, a chance at parole. Arriving on the island’s rugged shores, Carmen (Ena Hartman) finds two warring factions: one pseudo society that’s built little straw huts and stone structures and forced female inmates into prostitution. A second group of rogue outcasts is led by a more benevolent man hoping to free said women.

Against this appropriately daft premise and unforgiving backdrop, Rothman counters the masculine bent of exploitation cinema. The buxom women bound about in chambray cutoffs and perfectly calibrated Connie-Britton hair (the impracticality of which Roger Ebert couldn’t quite wrap his head around), but Rothman manages to inject the film with a keen sense of feminist ideals and ultimately envisions a universe free from the reign of patriarchy.

OLD

M. Night Shyamalan, 2021

Unsuspecting guests at a top-tier resort are trapped on a beach that causes them to age rapidly. The film camera eddies around them, birthdays and milestones achieved in the time it takes to twirl around in a circle. Shyamalan, low-brow poet and society-skeptic, turns a TV trope into the stuff of cinema, flashing on Picnic at Hanging Rock. The movie is diverting the way an amusement park is: an environment unto itself, providing unsophisticated, no-frills fun. The island is reliably stocked with Shyamalan totems, like mangled bodies and puzzle-logic, lying parents and authority figures. Viewing lost innocence with ambivalent distance, the film snarls at the world, but we lap it up.

I much preferred Old to KNOCK AT THE CABIN. Shymalan’s latest is compellingly perverse and wracked with a real sense of menace, making its hopeful denouement something of a betrayal. **SPOILERS** It seems a bit unfair that the well-meaning gay couple (Jonathan Groff and Ben Aldridge, barely given room to breathe), a proxy for progressive liberalism, must succumb to message-board posting zealots and sacrifice one of their own to ward off global annihilation for all.

GLASS ONION

Rian Johnson, 2022

Like its predecessor Knives Out, Glass Onion is largely a movie for children, populated by cardboard characters puppeteered to show what’s wrong with America today. Daniel Craig returns as Benoit Blanch, P.I. extraordinaire, in a role that would’ve gone to Kevin Spacey were he not an indefensible criminal. The film’s plotting is complicated but the emotional consequences are facile. A murder mystery party goes awry on a private island owned by an Elon Musk-like tech disruptor, endowed with greasy charisma by Edward Norton. Johnson, a huge film nerd, shows us what he thinks of the Twitter-owner by dressing Norton as Tom Cruise’s pickup artist character in Magnolia in a flashback. “Respect the cock!”

Janelle Monae, the other lead, is seventy times more magnetic than Ana De Armas was in the last film, and though actually solving the mystery on our own is out of the question, Johnson at least teases us with the possibility. If you’re watching carefully enough you can see Norton slip the glass of whiskey onto the table, for instance.

SWEPT AWAY

Lina Wertmuller, 1974

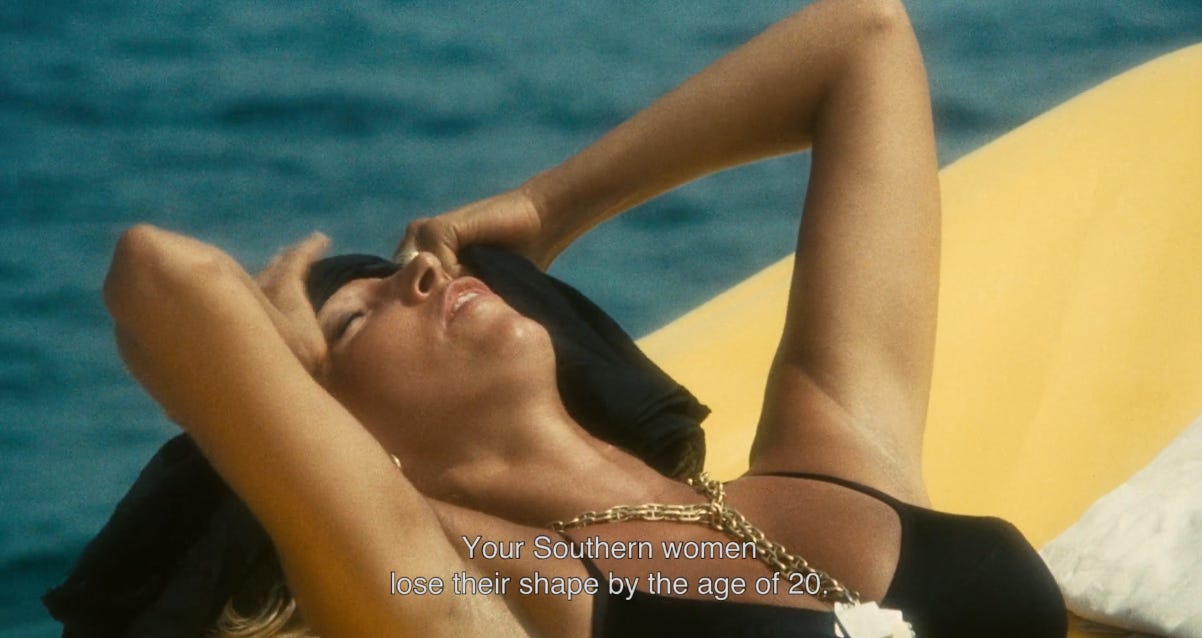

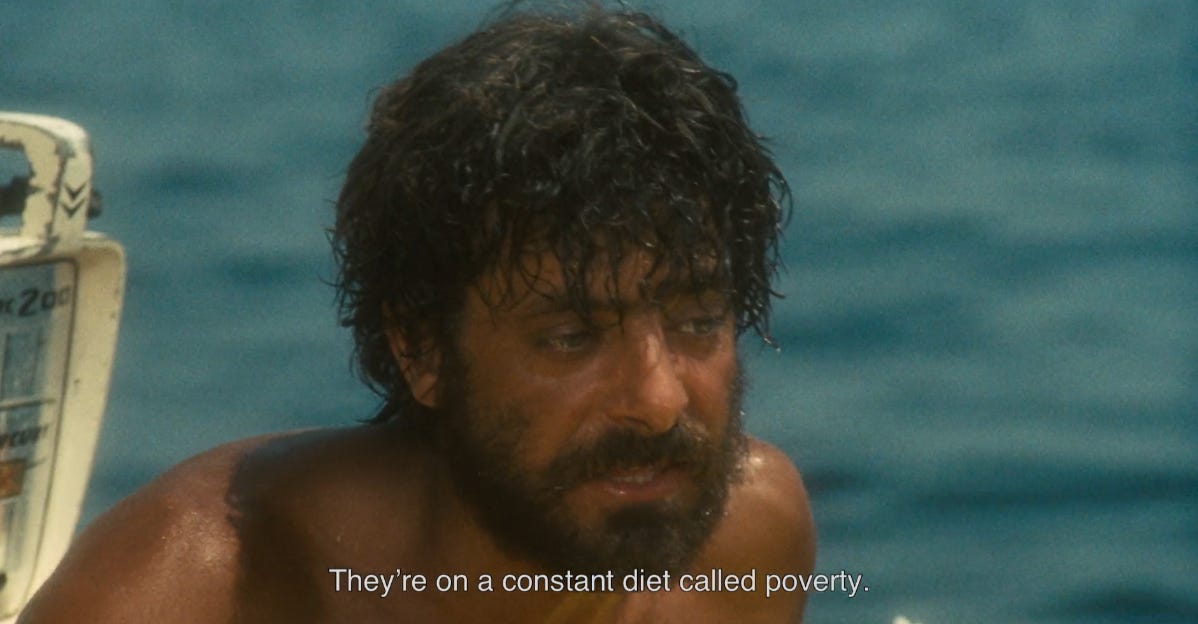

On a Mediterranean yachting vacation with her husband and friends, Rafaella (Mariangela Melato), tanned and fabulous, is shipwrecked with one of the deckhands (Giancarlo Giannini), rank, unshaven, and far less privileged. It’s difficult to tell how much this Real Housewife of Milan buys into the vitriol she spews, or bellows, really—Melato chatters with locomotive thrust—or if she’s just spitballing provocations against the working man.

Northerner and Southerner sizzle and hiss, trading vulgarities with withering force. Once they’re stranded, their hostility gives way to a complex and sensual relationship. The change of scenery prompts a role reversal, with power passing from the fascist patrician to the communist plebe. Softening her righteous stance, Rafaella becomes dependent on Giannino for survival and also victim to his sexual domination.

In scrutinizing Swept Away, one cannot overlook the scandalous sexual politics at play, but Wertmüller has a keen eye for the ways in which power and desire intersect. An avowed socialist, Wertmüller, made her career with astringent comedies exposing the body politic. What’s unquestionable is that sex is less about eroticism than it is about power, an allegorical inversion of the rich pillaging the poor. Swept Away is undeniably provocative, but doesn’t confronting something as filthy as money, as sullied as capitalism, demand such audacious treatment?

TRIANGLE OF SADNESS

Ruben Ostlund, 2022

Unfolding in chapters, Triangle of Sadness feels like three movies squashed into one, each less compelling than the last. While part of me is elated that the urban movie-going public have stepped out to a three-hour-long subtitled movie without any stars, the other part is disappointed. What starts as an examination of beauty as currency quickly evaporates into a wispily clichéd account of class warfare.

It’s all downhill from an exhilarating opening, in which the camera ogles a flock of male models oscillating from jolly smizes to blue steel scowls, as befits fast-fashion vs haute couture brands respectively. Historically, male models are severely underpaid compared to their female counterparts, so, why should Carl (Harris Dickinson), who is one of them, foot the dinner bill for his depthless Emrata-esque girlfriend (Charlbi Dean)? At a posh resto, the venerably knotty question abruptly escalates like a gas fire into an acute dissection of their relationship. She confesses to being in it for the likes; he declares to win her over in the name of true love. Force Majeure, Ostlund’s finely drawn 2014 film (remade into straight American farce starring Will Ferrell and Julia Louis Dreyfus), also homed in on romantic relationships, deftly poking around at a (cishet) couple’s evolving priorities, their obligations to each other vs. themselves.

Triangle of Sadness fails to achieve the same level of nuance. Midway through, a fancy yacht vacation turns, quite literally, into a shit cruise. The camera sways like a pendulum, creating a visceral sense of physical distress as the choppy waters rock the one-percent’s digestive systems into obliteration. Kudos, I suppose, to Ostlund for effectively making the most high-end advertisement for Dramamine.

As a smoothed reworking of Lina Wertmuller’s movie, Triangle is hardly revolutionary. The targets and jokes are familiar and thin, like a Russian plutocrat who deals in shit, that is fertilizer, and a pair of genteel Brits who happen to manufacture weapons. When everyone is inevitably marooned neither supplies nor skill, and an unexpected leader emerges: Abigail (Dolly de Leon), a Filipino maid or “toilet manager,” a crude term I’ve never in my live heard before. She arrives on an emergency boat stocked with Evian mist and pretzels, the most unpleasant snack one might consume on the edge of dehydration.

Her ensuing exploitation of lissome Carl could have been a powerful commentary on the intersection of race, gender, and class, but instead, it feels like a missed opportunity. Ostlund offers lofty cynicism in place of true critique, and a style that conforms to the the veneer of luxury (opulent interiors, steady takes, only as long as a novice would allow). Ostlund doesn’t want to eat the rich; he wants to eat with them.

Food is a powerful vehicle for exploring class divisions in Swept Away and Triangle of Sadness. Gennarino, in Wertmuller’s film, feasts on a lobster, a luxury likely beyond his usual means. A treat dating back to prehistoric times, the crustacean was adopted as noble delicacy as early as the 1300s. One of the first haute cuisine cookbooks suggested preparing it in wine and eating it with vinegar. (Lobster took a bit longer to catch on in America, where its colonial-era abundance led to its being used as fertilizer.)

The sailor’s ability to catch his lunch highlights his resourcefulness and self-sufficiency. Conversely, Rafaella's inability to fend for herself underscores her distance from the working-class experience. In another scene, despite ravaging hunger and need for sustenance, she forcefully recoils at the sight of a skewered rabbit—because, I imagine, she's never witnessed a carcass up-close, and not because she’s unfond of leporine game, which isn’t uncommon to the Italian diet.

Triangle of Sadness similarly emphasizes power dynamics, using octopus instead of lobster, like owning to the fact the it was filmed if not set in Greece. An abstractly plated tentacle comprises one of the dinner courses for the guests and inebriated Marxist captain (Woody Harrelson), though he opts for a cheeseburger instead. Here again is the unimposing charm of simple American food, meant to signify groundedness and working-class sensibilities. (The Menu also took this tack in its inescapable finale, built on compulsory nostalgia.)

Whereas the mismatched lovers in Swept Away share the lobster, briefly bridging the gap between their social classes, there is no such momentary transcendence of boundaries in Triangle of Sadness. Abigail wields her cephalopod bounty as a currency or prize, dangling it before the castaways and doling it out to those who pay their respects, prompting the rich at last to call for socialism.

OCTOPUS DISHES IN NYC

Octopus a staple in coastal communities and fishing villages all over Europe, as well as diets in Japan and South Korea. It hasn’t achieved nearly the same status as its shellfish brethren, and in the US it’s still harder to come by, outside the restaurants that specialize in said cuisines above. (Stumble into any Greek taverna or Portuguese spot, and you’re sure to see it.)

The most famous octopus dish in town is Marea’s fusilli, which finds nuggets braised in red wine. Topped with bone marrow, the dish neatly fits the ethos of Triangle of Sadness. I’ve yet to try it, but I’m sure it’s exquisite. Another iconic dish finds the tentacles thinly sliced in a sublime carpaccio at Txikito.

If you’ve never had octopus, you can ease your way into at Cafe Spaghetti, which serves it with potatoes in a traditional Italian salad(insulata di polpo e patate). The briny gaeta olives and the zesty oregano round of the flavors.

I took great pleasure in the simply prepared octopus kebab at Eyval in Bushwick. The sister restaurant to Sofreh focuses on Iranian street food, grilling over a combination of charcoal and wood.

EAT HERE: KONO

If these island movies restore a luxury food to its everyday roots, Kono, a high-end yakitori restaurant, does the opposite. It takes the commonplace good, the lowly chicken, and respectfully elevates it with an elaborate tasting menu.

Atsushi Kono, disciple of Michelin-starred Torishin, cooks sublime skewers utilizing every part of the bird over binchotan charcoal, not an easy feat. Without any stove dials, he must fan the flames to achieve the modulate the temperature. His mastery is evident in every dish, each cooked to perfection.

What you’ll have changes throughout the week, though you’ll almost certainly have a small cup of deep, concentrated broth to warm your palate, and thick crackly curls of skin to whet your appetite. I also had luscious oysters, those prized morsels of dark meat below the tailbone; velvety kidneys, so soft they nearly dissolved on contact; and knees, a bit too crunchy for my liking (the soft bone was a turn-off). If you’re lucky, you might get an ovary or testicle.

Of the many showstoppers, my favorite was the silky chicken liver, showered over with black truffles and pressed between monaka, rice wafers. It was like eating the world’s most exquisite savory macaron. For actual dessert was an ethereal creme brulee with Okinawan black sugar, lending a slightly salty and earthy profile in lieu of heavy-handed sweetness.

Located in an alleyway on Bowery behind a curtain, Kono has a speakeasy feel. Lo-fi beats like Nujabes trickled from the speakers. There are only a dozen seats or so around a spacious sleek bar and a booth for larger parties, all with a direct sight lines to the chef at work. The casual atmosphere can be a little too relaxed for the price point ($175/per person). The night I went, the place felt less like a special occasion spot and more like a major museum where whoever walks in with the breeze: fatcat regulars in t-shirts and tourists foiled by the weather.