Triple Feature combines one new movie / one old movie / one restaurant. Check out the first installment here.

THE BRUTALIST

Brady Corbet, 2024

Even at three hours and thirty-five minutes, The Brutalist glides. The sumptuous visuals, presented in VistaVision, a bygone film format last seen in Mary Poppins, gives the film a richness you can’t ignore (c/o cinematographer Lol Crawley). You don’t need a fancy film degree to appreciate that this movie looks like millions of dollars more than it actually cost. The Brutalist is an undeniably and endearingly classical film—the themes are sweeping and familiar: identity, legacy, art, commerce. Meanwhile certain flourishes—the casting of Ariane Labed, Isaac de Bankolé, and the use of erudite referential chapter headings that remind you of Von Trier—are there to remind you of Corbet’s adopted European heritage and art film sensibilities (i’m not necessarily complaining). The real surprise is how low on the scale of overt conflict the film rings. It mounts in the first act before trickling through in the second.

Adrian Brody reclaims his accent from The Pianist, for which he won an Oscar, as fictional Hungarian-jewish architect László Toth, who arrives in America as a Holocaust refugee. His wife (Felicity Jones) and niece (Raffey Cassidy) will arrive later to his home-cum-workplace in Pennsylvania’s steel country, where he eventually lands, given the opportunity revive his career under the patronage of Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a wealthy WASP industrialist who has hired László to design a sprawling community center in his dead mother’s honor. (The final product bears resemblance to Tadao Ando’s Church of Light and was a feat by the film’s production designer Judy Becker.)

László is Van Buren’s pet project, constantly reminded of his status as the artist owned by the rich benefactor who, incapable of being an artist himself, buys the privilege of owning one. He is likes to show László off and remark how intellectually stimulating he is in front of his guests. Pearce is a notch over the top in the smarm department but it worked for me. (If we learned anything from Vox Lux, it’s that Corbet welcomes a little overdetermination in his performances. Pearce’s Van Buren lives in the same realm as Natalie Portman’s forcefully blowsy pop singer from Staten Island in Vox Lux.) Meanwhile Felicity Jones sounds she’s doing an impression on Saturday Night Live.

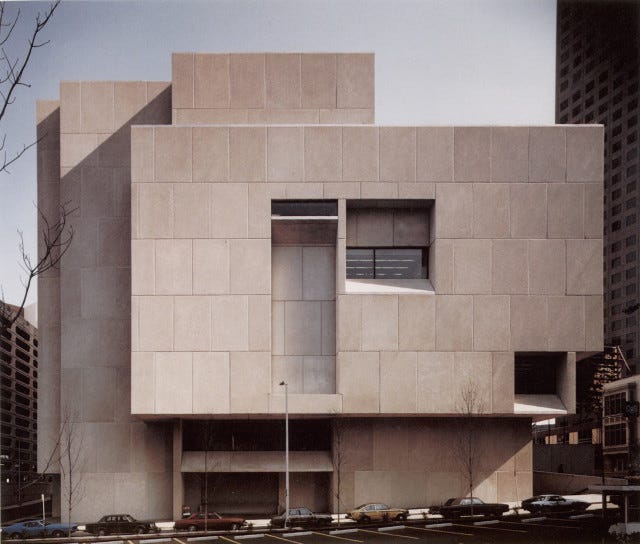

For a movie called The Brutalist, Corbet does not excavate the historical context of this architectural style. Emerging after World War II, Brutalism reflecting the era's desire to rebuild society with functional, minimalist designs. It aligned with socialist ideals, symbolizing equality through large-scale public housing while rejecting elitist styles of the past. (The austere designs also reflected the harshness times, and this cold impersonality became synonymous with bureaucracy and state power.)

Corbet mostly ignores all of this, choosing instead to hone his focus on the architect as a job. And that is what really endears me to this film. Most people—and movies— romanticize the profession, miscategorizing it as an intellectual and artistic one, like a painter at an easel. I pictured something along those lines before I met my husband1 when I was hit with the reality that working in architecture is akin to publishing, characterized by relentless labor and minimal reward, where the fruits of your toil may only be recognized once your name graces a building. (The disagreeable all work no pay conditions are why firms have begun to try to unionize.)

The Brutalist rather brilliantly takes the struggle to achieve American dream and maps it onto the architect’s reality, revealing to us how those in the profession are seldom portrayed—not as lofty creators but as overworked, merely tolerated laborers tethered to the capricious whims of whoever holds the checkbook. They are not draftsmen behind a desk but middlemen on site, whose only way of protecting the integrity of their design from being debased by cost-cutting value engineers is maybe through self-sacrifice. Lazlo gives up his fee. (architects are at least partially paid based on the total cost of the project, another reason to cut expenses.)

Even after Laszlo achieves fame and retires, we can assume he remains at the mercy of curators and institutions who seek to shape his legacy as seen in the last few scenes. The dynamic is on par with filmmakers, juggling financial backers, contractors, tight schedules, and the myriad moving parts, and no doubt part of Corbet’s modus operandi in telling this story.

Laszlo comes to America because, as Erzsébet, his wife, remarks, there is nothing left for them in Europe. Yet in the land of opportunity, what awaits these Jewish immigrants but the harsh realities of suffering and antisemitism. For his niece, the answer lies in Israel, a place that offers a new kind of hope—fraught with complexities that Corbet explicitly entertain in the film. For more on that and the film in general—here’s Mark Asch for The Art Newspaper and Noah Kulwin for Screen Slate.

The Brutalist evokes films like There Will Be Blood, The Master, and The Godfather, but its denouement betrays an uncertain tone, caught somewhere between a shrug and a 'fuck you'—if that. The film is less like a tightly woven narrative and more like an anti-epic, elastic to your own interpretation—maybe too open, and therein lies the flaw. Depending on where you stand, The Brutalist is either contrived or complex, and critics exaggeratedly talk of Corbet as either the savior of cinema or a self-indulgent try-hard. I think we can cut the difference.2

TLDR: If it wasn’t clear, I still like this film and think it’s very much worth watching. I saw it twice.

MORE BRUTALISM IN THE WILD

THE DEER HUNTER

Michael Cimino, 1978

Hear me out. This film is yet another epic with a lengthy runtime, capturing a significant historical moment in America with some embellishments. It is a Big Themes Movie painted in broad strokes, with an ending more puzzling than the director intended, interpreted in diverging political ways. It might also have been titled The Brutalist.

BRIDGES

9 Chatham Square, Chinatown

Last fall, Bridges was the name on everyone’s lips, hailed as the best new spot by a select group of tastemakers and cool kids—think Sue Chan, Chris Black, and friend-of-the-newsletter

. This, despite the fact that it didn’t appear on any official lists. It likely would’ve made mine, if I had one.The chef behind it hails from Estela, but this is not an Ignacio Mattos venture. The menu encompasses many facets, flavors, and interpretations—though, apparently, the cuisine it’s meant to evoke is Australian. The restaurants design introduces light touches of Brutalism, with its concrete walls and green glass, bricks but unlike the austere architectural style, the food is remarkably inviting—delicious in a way that belies the space’s stiffness. In that, it mirrors Corbet’s films.

An auspicious beginning: an electrifyingly tart macerated wine. Zach and I whispered that it tasted like Vej, one of the favorites in our rather limited vino repertoire. The observant server overheard and politely, enthusiastically confirmed, leaving us smug with our assessment.

I experienced the conspiratorial delight with dessert—vin jaune gelato. (Vin jaune, a wine from sauternes, seems to be having a moment as of late.) The alcohol only comes to a head later, dancing on your tongue after the full-fat lushness of the cream. It’s not your boozy milkshake, more like zingy fruit that explodes further with the crunch of a thousand passion fruit seeds scattered on top.

The Comté tart is rave-worthy. A minimal amount of cream binds the custard together in this lush piece of savory pie, decorated with mushrooms sauteed in wine (there’s that vin jaune again.) I like to think the elegant dish, landing somewhere between flan and quiche, is what Vicky Krieps would have served Daniel Day Lewis in the Phantom Thread. It is sexy but rustic and delicious enough to distract from any potentially harmful effects.

Meanwhile, the texture of the grilled sweetbreads falls between octopus and kubideh, boasting a nice char. When punctured, they release a steady flow of juice, and if you wrap one with a leek in lamb’s quarters and dab on some mustard, it’s almost as if you’re having a fusion French-Korean bbq ssam.

If you’re a fiend for oily, silvery fish, you’ll be roused by an appetizer that ornaments toast with sardines and anchovies. The fish is stubbornly fish, and the toast is tiny.

Duck is something that usually gives me pause, but the one at Bridges is weepingly good. The breast is laquered with an apple jam and seared; the leg was crumbled into a grape leaf. These disparate bites—the portions aren’t small but you will remember them—have come to redefine the bird for me altogether.

The accompanying potato puree is whipped into airy as only I've seen my mother do. Except she uses a fifth of the amount of butter that Bridges does. The XO sauce plopped on top is neat I suppose, but mostly a distraction, an umami bomb that shatters everything in its wake.

The flavor combinations can seem odd and disparate at times. But even when they fail to blend seamlessly; they don’t upset any balance either. Take, for instance, the punchy, crackly smoked eel dumplings. The golden broth they’re served in is rich and minty like an icy Maine wind sweeping on top of chicken soup sweeping over a bowl of chicken soup. It’s at once saline, hearty, and herbaceous, owing to pickled sakura leaves.

Best for: Dinner with sophisticated friends and lovers, taking out cool parents.

Aside from the Comte tart, I’ll order everything else differently when I return—not because what I ate was lacking, but because but I firmly believe that the rest of the menu will be just as excellent.

Next time: Valentine’s day movies; Short Takes; honest of all the Oscar nominees.

➻❥

In case you missed it

9 movies about houses— and Bar Quarters

In high school I became obsessed with this idea of making a film about an empty house, likely stemming from the fact that I moved around a lot as a kid and my parents were not homeowners until just before I left for college.

The problem with Babygirl

In the opening moments of Babygirl, Nicole Kidman’s character slips out of bed after having sex with her husband. She sprints down the hall to final destination, her enviable walk-in closet, large enough to hold her prone body as she furiously masturbates to some good-girl-for-daddy porn on her laptop. Nothing that follows in the film—a tale of middle-a…

Zach and I keep a running list of architect movies.

Corbet’s previous films have revealed him to be a smart and studied provocateur, who can soemtimes veer into affectation. But for me The Brutalist almost felt too earnest, which then became its own affectation I guess

I do thing that Guy Pearce was incredible in that role and smashed that performance, going from this charming and "open" character to a dark personality. The end was a bit un-emotional and I did't really understand who the woman was at the end, speaking. I was trying to figure out who it was and missed kind of what she said... One thing that stuck out for me was the sound and music. Super well done and creative. Anyway, I think it is a great movie.

“Too open” definitely resonates with me. I enjoyed it, am happy it exists & am glad I saw it with the concentration a movie theater requires, but afterwards when my friend and I were munching on poutine we just kept finding ourselves trying to justify the existence of characters and scenes that were stilted or unexplored.